“When the well is dry, we know the worth of water,” said Benjamin Franklin. As India faces one of the worst water crisis in recent times, and news of Chennai’s water shortage dominates headlines, the saying seems to be proving true.

Chennai isn’t the only place facing a water shortage. Much of India is reeling under this devastating drought. According to the Indian Meteorological Department, the country’s overall monsoon rainfall deficit was 43% until last week, and several states including Maharashtra, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, and Uttar Pradesh (about 500 million people) are grappling with drought and farmer distress. In early June, water levels in 91 major water reservoirs plummeted to 20% capacity. This historical drought coincides with completion of the Lok Sabha (India’s lower house of parliament) elections and the swearing in of the new government. Like previous elections, water was a key issue covered in major political parties’ manifestos. Already, post-election we’ve seen some movement on those political promises as the new government created the Ministry of Jal Shakti, which consolidates water-related roles and responsibilities previously divided across three ministries Having a single ministry with a total focus on water is a great first step, and now it is time to roll up our sleeves and get to work. ISC has been working closely with the manufacturing and agricultural sectors on water stewardship, and based on our on-the-ground experiences recommend the following areas of focus to make major headway on an urgent threat to the vitality of India.

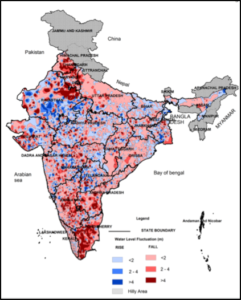

Groundwater management: Groundwater is the major source of irrigation and drinking water in India. In fact, India uses more groundwater than China and the United States combined. An analysis of groundwater level fluctuation (2007-2017) indicates that around 55% of the country recorded a decline in water levels (Figure 1).

For a country so deeply reliant on groundwater it is critical to not only limit groundwater extraction, but also find ways to incentivize methods and practices that keep water in the table. Approaches like rainwater harvesting can reduce drought and mitigate flooding, but haven’t been adopted at scale.

Source: Central Groundwater Board

Improving water use efficiency: Improving water use efficiency will not only address the immediate crisis, but is crucial for reducing dependence on freshwater sources for long-term impact. For example, the agriculture sector accounts for more than 85% of India’s freshwater use; however, the sector’s water use efficiency is less than 30%. We can improve this by driving adoption of low cost technologies and practices, which we know save freshwater without impacting productivity. The capacity of all sectors must be built to engage in appropriate water use efficiency practices. Setting up a Bureau of Water Use Efficiency would make sense as a first step to coordinate these efforts.

Managing industrial water risks: Indian corporations, their investors, and policymakers have significant responsibility to treat water with the strategic importance it deserves. The demands of rapid industrialization and urbanization come at a time when, due to climate change and pollution, water tables are falling and water quality is deteriorating. To achieve sustainable water development, industries should regularly audit their water use, and water intensive industries such as paper and pulp; textiles; food; leather; chemical/pharmaceutical; oil, gas and mining should consider both quantity and quality of water. We should be seeking ways to incentivize this type of proactive water stewardship, such as making the business case clear to these industries. Clean, plentiful water and healthy workers are in the economic self-interest of industry.

Promoting the use of treated wastewater: Wastewater from India’s towns and cities may cross 120,000 million litres per day (mld) by 2051, and rural India will generate more than 50,000 mld. While we take measures to increase treatment capacity, it is important that more attention is given to promoting the use of treated wastewater for irrigation, non-potable use in cities (horticulture, dust suppression) and industries.

Currently, the option of a dual water system is being examined in several parts of the country. These systems bifurcate water supply based on use – with filtered purified water for drinking purposes and a lower-quality source of water used for everything else. This approach also saves costs as fewer resources are used cleaning water.

It is often said that a tough situation calls for tough measures. Government initiatives over the past few years demonstrate the desire and capacity to proactively address water-related challenges, and Prime Minister Modi has outlined water resources as an area of priority for the new government. Balancing the competing water needs across states, sectors and users will not be easy, but people will look to the government to fulfill the expectations pertaining to a fundamental resource to life – water!

In our work, we’ve seen that this is possible, and that cooperation and engagement across different stakeholders will be the key for ensuring water security and sustainability in India and beyond.