Why are the buildings we live in so important? Communities are built on people, but also on the places where people live, work, and exist. Buildings are important because we spend most of our time in them, and they give us a sense of place, identity, heritage and home. But buildings that are not maintained or up-to-date can also hold us back and even cause harm if they are not functioning properly.

Modern St. Louis has one of the world’s most iconic skylines thanks to the Gateway Arch, the tallest monument in the U.S. in the smallest National Park. It proudly hearkens to our place as the proverbial “Gateway to the West” but also hides deep wounds in the city’s history.

Segregation of People and Buildings

Fragmentation continues to divide us and segregate our residents along municipal boundaries, both geographic and cultural:

- The city itself is built on the convergence of two great rivers, where native societies— like the Mississippians and others—built great earthen mounds that stood as enigmatic reminders of their heritage even after their other structures returned to dust. As the city grew, however, the mounds were leveled until only one lone mound remained.

- The Old Courthouse is also where Dred Scott sought freedom from slavery for himself and his family. In St. Louis, they prevailed, but the U.S. Supreme Court followed in 1857 with a devastating rejection and the edict that people of African descent were not American Citizens.

- The Old Courthouse stands as a remnant of the “Great Divorce”—when St. Louis County voted to separate from the City of St. Louis in 1876.

- A decade ago, Michael Brown’s killing in Ferguson—located in St. Louis—made waves across the nation. It is a harrowing example of how easily the concept of place can seemingly insulate or contain the bad while regional solutions belong to no one.

- Through desegregation programs, St. Louis Public Schools, century-old architectural marvels, have been left underfunded for decades.

Racism and Building Emissions

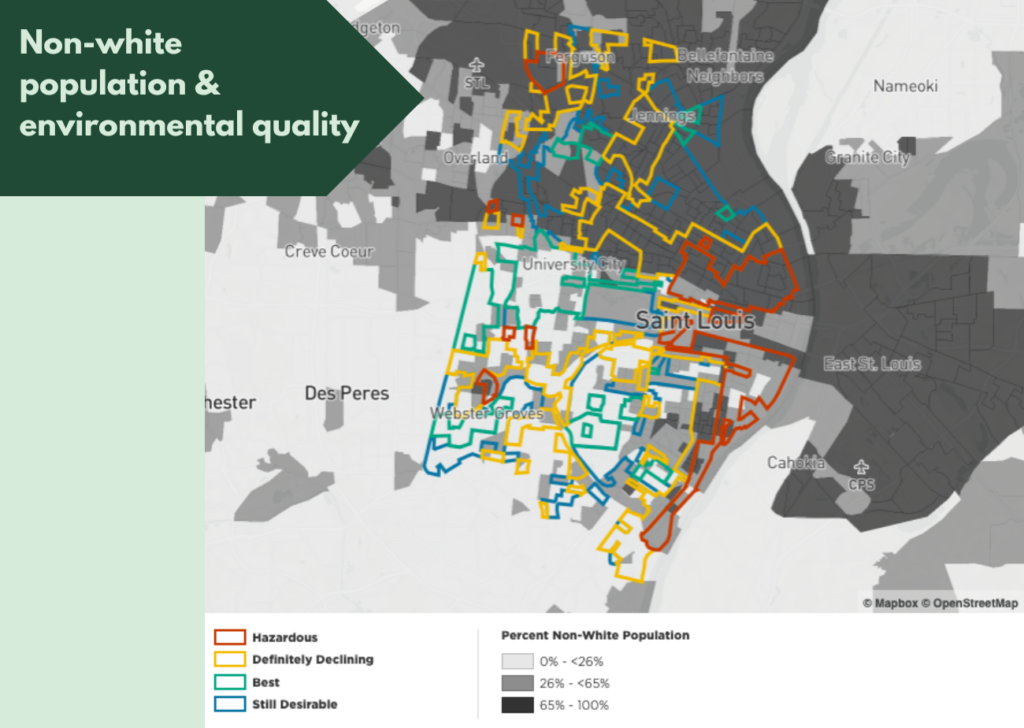

All communities do not have the same access to resources or opportunities. It isn’t just the buildings that are central to this story, but also systemic failures through the intentional targeting of communities of color. These practices led directly to the locational demographics and problems of today’s St. Louis while postponing real investment and opportunity for our communities.

Like many other places, St. Louis experiences inequity in housing—through energy efficiency, utility rates, energy burden, and even housing agency. ISC’s Building Decarbonization & Equity blog highlights how certain groups of people—and particularly people of color—face significant barriers to housing that is both affordable and energy efficient.

What are the Barriers to Efficient Buildings in St. Louis?

There are many factors that lead to inequities in buildings. In St. Louis, these include:

Energy Burden

- St. Louis experiences energy burdens 86% higher than the national average

- The energy burden on the 20% most burdened communities is 3 times that of the 20% least burdened communities

Why it matters: Households spending higher percentages of their income on utility bills may be unable to afford energy efficiency improvements, as well as other resources, such as food.

Property Values

- Neighborhoods with more Black residents are perceived as less desirable by both white and Black individuals in St. Louis

- The highest vacant property rate in St. Louis is in a historically Black neighborhood, and 60% of the properties in the area are vacant

Why it matters: Less desirable neighborhoods often equate to declining property values. When the cost to upgrade or repair a property is higher than the property’s value, it can be challenging to receive a loan to finance the work needed to make a property energy efficient.

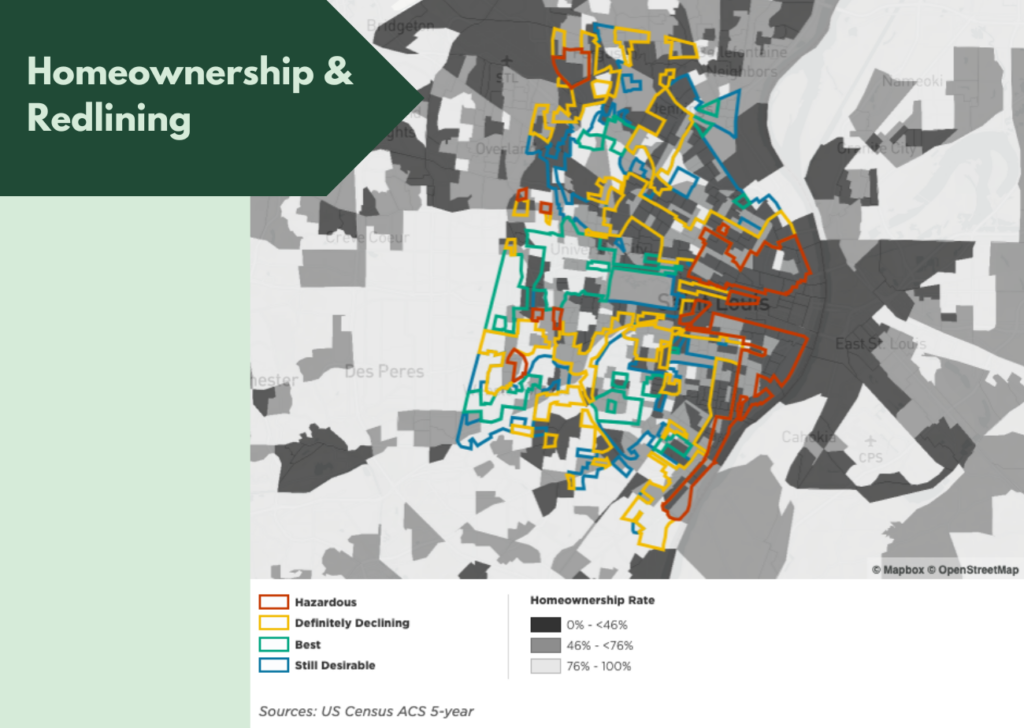

Redlining and Systemic Discrimination in Housing

Redlining in St. Louis affected which families received mortgage funds to purchase homes—between 1934 and 1962, 98% of mortgages were given to white borrowers

Expressways were built in over 450 acres of residential majority-Black neighborhoods

A 2016 report found that while white residents are 75% of the St. Louis population, they received 83% of the mortgage loans. In contrast, Black residents are 18% of the population, but received only 4% of the loans

Black renters in St. Louis are more than twice as likely as white renters to spend over 50% of their household income on rent

Why it matters: People of color have been deliberately excluded from buying their own homes, and as a result, are more likely to rent. Landlords may be unwilling to pay the upfront costs of installing new technologies, or may raise rent after making improvements.

Public Health

- Five counties in Missouri—all in the St. Louis area—currently experience ozone smog levels that exceed EPA standards

- Extreme rainfall has become 53% more frequent in Missouri over the past 60 years; at the same time, storms have grown to contain 20% more rainfall. These heavy rains not only increase the risk of flooding, but can also lead to drinking water contamination and disease outbreak

- In 2011, St. Louis County experienced 69 extreme heat days; by 2080, 93 such days are projected to occur

Why it matters: The most vulnerable populations are the most at-risk for the negative health effects of pollution, climate disasters, and extreme heat.

All of these statistics are tied to our buildings, meaning that our ability to have agency in our lives is also directly tied to the buildings in our communities. Limited options, especially for those in poverty, create competition for cheaply built, old and inefficient spaces. The paralyzing separation of who provides the investment and gets the reward is a split incentive, and causes a lack of agency in making decisions about buildings.

When coal was the source of heat for St. Louisans, we faced blackened skies and breathed at least an ounce of soot daily. We mostly cleaned up the coal smoke in the 1940s, but we are still at great threat from the effects of climate change. Buildings run every second of every day—making up 80% of St. Louis greenhouse gas emissions—and we interact with them constantly. We must approach building emissions (and reducing them) in the same way. By using renewable energy, improving energy efficiency, and improving access to green financing, we can both reduce emissions and create healthier, more affordable housing in St. Louis.

About the Author

Malachi Rein is the Director of the Building Energy-Exchange St. Louis since September 2022. He has a B.S. in Architectural Engineering from Missouri S&T and an A.A. in Communications from St. Louis Community College. He brings experience in facilities management, operations, and project management.

Rein has a passion for creating a more sustainable built environment. He is a LEED AP BD+C and holds certifications through GPRO Operations and Maintenance Essentials and Building Operator Level 1. A lifelong resident of the Saint Louis region, he firmly believes that our buildings matter and that we can empower positive change that impacts our balance with our planet and the lives of real people.