Opportunities for a Gender-Equitable Energy Transition Through Female Leadership

February 23, 2023

Authors

Terms like “sustainable, “renewable,” “clean technology,” and “climate friendly” have become buzzwords for businesses in our current day and age. Countries and large companies are pledging to combat climate change by switching to low-carbon operations with a goal of becoming net-zero emitters across their value chains. In an attempt to ensure a just transition, team members from the Institute for Sustainable Communities (ISC) spoke with small and medium enterprise (SME) owners and managers across India to identify opportunities for a gender-equitable energy transition through female leadership. Owners, managers, and human resource departments of more than 40 textile units, chemical factories, food processor units, and auto component manufacturers across Gujarat, Maharashtra, and Tamil Nadu were interviewed. Much to our surprise, amongst all the companies visited for interviews, only one leadership position was held by a woman, who we refer to as Lakshmi going forward to protect her anonymity. Although it was refreshing to interview a female SME owner, it was equally astonishing to understand the reality of India’s manufacturing sector and the depth of its gender inequity. While speaking to Lakshmi about the barriers she faces on a daily basis, the manufacturing sector’s inherent bias towards men became increasingly evident. From lack of access to a STEM education to finding employment in unconventional or non-stereotypical jobs and challenges moving up the career ladder with equal opportunity, women face roadblocks at every step of their professional journey.

Female Participation in Manufacturing SMEs

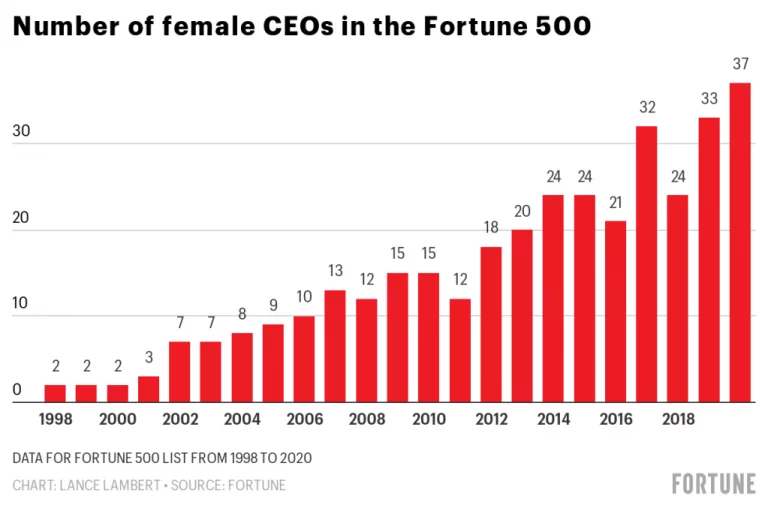

In India, female participation in manufacturing SMEs, especially chemical and automotive sectors, is shockingly low.[1] When the word ‘manufacturing’ comes up, people envision cumbersome jobs that involve lifting heavy machinery and working in harsh factory conditions. This leads to a common stereotype that the manufacturing industry is only suitable for men, be that owners or workers. India’s female labor participation rate was only 20.3% in 2021, ranking among the lowest among emerging economies.[2] Since the emergence of COVID-19, most of the jobs lost were those held by women, mirroring trends seen worldwide. Female employment in India dropped to 9% after the COVID-19 outbreak.[3] Meanwhile, the number of women CEOs at Fortune 500 companies has risen by 1900% over the past 20 years [4] and the global percentage of women in senior management roles increased to an all-time high of 31% in 2021.[5] While 10% of the CEOs of Fortune 50 companies in the United States are women, only one Indian company amongst the 50 companies, HDFC Life Insurance, has a female CEO. According to the 2020 Fortune India 50 rankings, only one organization, SAIL, has a female as chairperson. In 2019, just 29 (6%) Indian Fortune 500 companies had women leaders in executive roles. With most of the world accelerating the number of women in leadership positions, India has the opportunity to follow suit.

Unfortunately, female SME owners are less likely to be taken seriously and followed as leaders, despite the fact that they face far more barriers and have to overcome more to prove themselves to reach leadership positions compared to their male counterparts.[6] In one interview, the manager of a SME stated that female engineers and women in leadership positions are not taken seriously. Another SME manager said that male workers often do not respond proactively or positively to female supervisors. This reflects on the nature of power dynamics and inherent gender biases resulting from a patriarchal mindset of the society. It holds especially true in rural areas and the economically weaker sections of society that form the major workforce of the Indian SMEs. Lakshmi confirmed this sentiment explaining that as a woman in a leadership position she has to be cautious of her tone in the workplace because it is easy for women to be viewed as bossy and hard to work with if they are strict and firm, yet being more gentle undermines their credibility and leadership. There is a lack of acceptance and trust in women’s capabilities as leaders, which again reflects the deep-rooted gender biases.

Maintaining the position of a female leader in the manufacturing sector is just as difficult as obtaining it. Sixty percent of factories interviewed only employed zero to five women in leadership positions. However, exceptional cases from around the country are invalidating the excuse that women are not capable of working in manufacturing. An excellent example is MG Motor India’s Vadodara facility where one of their automobile manufacturing units has an all-women crew that is responsible for end-to-end production.

Female Role Models Break Stereotypes and Bring Equity

With a woman SME owner, it is likely that the hiring and training process will become more gender equitable. This is because women bring new, broader perspectives to the table and understand gender discrimination and inequity at a deeper level. As stated by Marian Wright Edelman, “You can’t be what you can’t see.” Furthermore, a female role model helps break gender stereotypes, enhancing the possibility of increasing female job applicants. Research also shows that role model intervention has a significantly positive impact on girls choosing STEM career paths and expecting success in the field. [7]

Establishing Gender Equitable Work Environments

In conversations with male SME owners, there was an unwillingness to fund facilities for women since the added expense is not viewed as a worthwhile expenditure. Conversely, Lakshmi has direct experience with the needs of women working in the unit and the importance of these facilities. First-hand experience may increase the possibility of allocating funds for creches, prevention of sexual harassment (POSH) committees, separate toilets, sanitary napkins, transportation, and other necessary facilities. In fact, the cleanest women’s toilet was located in the SME with a female owner. In most other factories, female toilets were operational only on some floors and in barely decent conditions.

Some male SME owners share a fear that the presence of women distracts men and increases the risk of harassment cases. Anecdotal reports tell of some instances in factories where attraction or relationships led to cases of harassment. Of the factory owners interviewed, 76% claimed that challenges such as errors in production and time wasted due to prolonged conversations between men and women in the same production lines are issues that have to be addressed. This points towards the importance of requiring gender sensitization training of factory workers and managers to help establish gender equitable work environments.

Increasing Female Worker Participation to Solve High Attrition Rates

The issue of high attrition rates of employees could be minimized with an increase in female worker participation. Eighty-five percent of SME owners and managers claimed that men have much higher attrition rates than women. More than half of this group believe that women are more stable employees than men. High female participation in the workforce could lead to monetary benefits from lower skilling/reskilling required due to low attrition rates. This, compounded with increased female SME managers or female leaders, could likely increase the possibility of women workers being promoted and upskilled. By increasing the chances of career advancement, women can progress rather than remaining stuck in low-skilled jobs.

Women Supporting Women: The Need for Gender Sensitisation

Although women leaders are expected to positively influence the workplace, this may not always be the case. On-ground surveys highlighted that women are not always supportive of creating a positive environment for other women. This comes from a deep-rooted subconscious bias that new women workers should deal with the same hardships that women before them had to overcome. The practice of employing only menopausal or unmarried women is just as acceptable to female owners and managers as it is to men. Echoed by most gender-equity experts and SME owners, the importance of a change in mindset and gender sensitisation of both genders, cannot be stressed enough.

Gender sensitization, government mandates, or company-level interventions…what will be the most effective path forward? Who should take responsibility to fight for gender equity? These questions remain unanswered. What can be said unequivocally though is that immediate action to involve the women of India in the workforce is crucial for a gender-equitable, sustainable future.

[1] Institute for Sustainable Communities (Livelihood assessment and skill development for sustainable manufacturing in India) Manuscript under review.

[2] https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.TLF.TOTL.FE.ZS?locations=IN

[3] https://www.livemint.com/news/india/female-workforce-in-india-declined-to-9-since-covid-pandemic-here-s-why-11654254827989.html

[4] https://insideiim.com/women-ceo-fortune-500-companies

[5] https://www.catalyst.org/research/women-in-management/

[6] https://www.babson.edu/womens-leadership-institute/diana-international-research-institute/research/beyond-the-bucks/