The COP26 commitments seem achievable, appropriate, and right on time. Yet, to up the game, India needs to ensure that the clean energy transitions are people-centered and inclusive, with actions that build equitable and sustainable models for universal access to modern energy.

To accelerate climate action, for the first time after the Kyoto Protocol in 1997, fossil fuel was mentioned in the COP draft text. Many see the two-week negotiations around fossil fuel as a ‘complete flop’ and point at India and China- two of the largest emitters, for not taking bold steps. It is unfair to call out India since the US and China had embraced the coinage’ coal phase down’, negating India’s insistence on equitably reducing coal dependency. Also, it cannot be denied that India is the only G20 country that is well on track to achieve its nationally determined contributions fixed under the Paris Agreement.

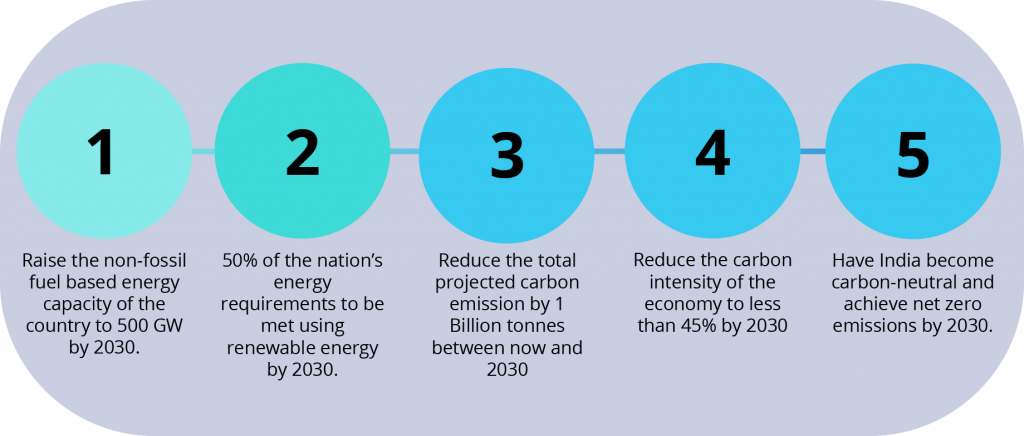

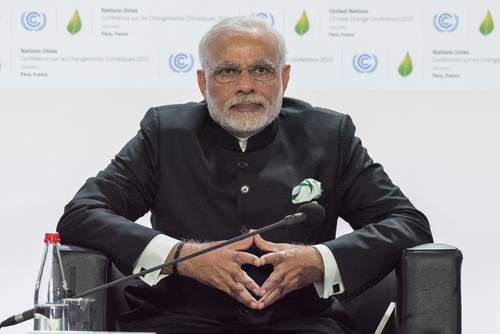

India reaffirmed the continuation of key principles from the Paris Agreement and made a series of significant commitments to translate commitments into rapid action to tackle climate change. Prime Minister Narender Modi’s five nectar elements, outlined in his Panchamrit speech in his National statement at COP26, showcased the country’s preparation to deal with the crisis and ensured that work isn’t done in silos. India’s 2030 commitments are clear: achieving installed renewable energy capacity of 500 GW; meeting 50% of electricity requirements by renewable energy; reducing cumulative carbon emissions by 1 billion between 2020-2030; and reducing the carbon intensity of GDP by 45% from 2005 levels.

These are huge commitments from a country that contains one of the largest populations in the world (United Nations 2019), 2.4 per cent of which still don’t have electricity in their households (IRES, 2020)– and a prediction that carbon dioxide emissions will peak between 2040 and 2045. However, there is evidence that various stakeholders across the nation are building readiness towards clean energy and decarbonization.

The infamous industrial sector has come forward and approximately 11 large Indian firms have already committed to Business Ambition for 1.5°C; 355 non-state actors have signed up to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change’s (UNFCCC) race to zero campaigns. Private companies are shifting to manufacturing electric vehicles (EVs) and investing in infrastructural change for easy adoption. To accelerate the progress, a recent announcement from IndianOil to install EV charging facilities at 10,000 fuel stations over the next three years was made in early November. From pushing electric mobility at a national scale, to envisioning a single global grid interconnecting 140 countries each dispatching and sharing solar energy, India is taking crucial steps to combat emissions.

This wasn’t the only important takeaway from Prime Minister Modi’s speech. The Indian Space Research Organization (ISRO) has already developed an android application that could compute potential solar energy at any point on earth and calculate the location’s realistic solar potential. This application will help decide solar projects’ location and further strengthen the ‘One Sun, One World, One Grid’ (OSOWOG) commitment under the India-UK coalition; Green Grids Initiative. India already shares transmission capacity for energy transfer across borders with Bhutan, Bangladesh, Myanmar, and Nepal, which can be expanded further and utilized to transfer solar power post feasibility study. The project will use battery storage to make round-the-clock dispatches at considerably cheaper rates than a coal-based generation. Large, affordable batteries will be essential in detaching the global economy from fossil fuels. To make the implementation trouble-free, battery technology is improving and rates have been falling since 1991 (around 97%).

Presently, India has 155 GW, ie. 40% (CEA) of its power capacity coming from non-fossil fuel and it has come a long way in building infrastructure for solar energy while simultaneously advancing the wind energy sector. The wind energy industry is capital heavy and the Government has provided many incentives, such as income tax exemptions on profits from power generation for the first 10 years of operation to excise duties exemption on solar components and inter-state exemption charges for 25 years. Among various clean energy technologies India is also exploring low‐carbon hydrogen as a key driver to support the country’s clean energy transition. It has demand and potential. However, such initiatives need to be backed by finance, and the necessary policy interventions. India needs $15 billion in funding to set up 15 GW of green hydrogen electrolyser capacity by 2030, and there is a deficit in terms of financial support from developed nations. According to the report by Climate Policy Initiative, against the required USD 170 billion per year, the total green finance for climate action over the last few years stood at a little over 10 percent (about USD 19 billion on average) across sectors. With several leaders committing to close the climate finance funding gap and new pledges by developed countries, countries have worked to increase their climate finance and bring in some hope. Furthermore, through the Glasgow Finance Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ), over $130 trillion of private capital is now committed to transforming the economy for net zero over the next three decades. However, the climate finance plans announced by developed countries to support developing countries need to be more accountable and scale up long-term finance support, and aim to enhance annual flows that are three years behind schedule. In the meantime, India can leverage the available biodiversity to create opportunities for climate finance via monetising on neutralization plans, which generate green jobs and reduce climate injustice. The country also needs to formulate a detailed target-based plan for climate action and a pathway to Net-Zero to take advantage of the full range of green financing opportunities available.

The COP26 commitments seem achievable, appropriate, and right on time. Yet, to up the game, India needs to ensure that the clean energy transitions are people-centered and inclusive, with actions that build equitable and sustainable models for universal access to modern energy. India needs to focus on human development and strengthen just transitions for the economy’s workforce to be green job ready by 2030. With the 2070 net zero commitment, there is further scope to work on how the country sustains a net zero status quo on a community level. There needs to be a bottom-up approach to the net-zero journey that links aspects of the sustainable energy transition to social and economic goals; avoiding cross-cutting policies. The Institute for Sustainable Communities (ISC) believes communities, their people, and their institutions can create change when they have the right knowledge and skill, strong connections, effective institutions, investment opportunities, and the ability to access and test solutions. To integrate ambition with a holistic approach, it is important to rationalize targets by integrating social dimension at a planning stage, creating synergy among partners and relevant stakeholders. Regional multi-stakeholder committees comprising sector-wise subject matter experts can be formed to build the momentum, integrate social dimension, advance conversation, review the process, ensure credibility, assess the progress and implementation of the plan of action through robust monitoring and evaluation.

1. https://ourworldindata.org/battery-price-decline